Fear not, for this is the Word of God.

Tremble instead at the silence that follows.

So said the speaker, muffled itself by the static of angels.

The Word sang alongside an electric chorus.

Surrounded by wires, the man repentant sat

raptured by screens.

The last Light screamed from diodes.

Backlight bathed him in taunting vollies.

Clutching at cables gone cold,

he prayed to dead pixels for pardons never promised.

Do systems sing in hushed tones? Preaching in signals

unencoded, but seldom rendered?

Tears, caught in cameras and sanctified in scripture,

unfurled through the techniques of laws well-known.

Salvation sprang not from the lenient scapes of content

but was erected out of pious processes, each more terrible than before.

Go then, and hear the familiar hum,

then listen loudly to the excruciating silence.

"The bringing into cultivation of waste-lands" - Marx

The wind screams to nothing as absence rests heavily atop a rocky plain. No one dares venture here, not because of anything in particular, but of what it lacks. What landscape is more indicative of the end times than the wasteland? Lighting screens of a dark tomorrow, wastelands paint a bleak backdrop to films depicting harsh environments or the aftermath of a terrible disaster. The deserts of Tatooine or the visions of McCarthy's The Road seem to contrast our inhabited and shining pathways from city to city or suburb to exurb. Yet, the wasteland is here and it is in New Jersey.

First, continuing our speculative project of the apocalypse, the end of days was yesterday and rather unceremonious. With this in mind, the wastelands of this brave, dead world are equally banal. On the route out of New York City, if one dares cross the GWB or tunnels beneath the Hudson, they are met by a nightscape of parkways and turnpikes, tolls and taillights, all illuminated by the light pollution of near cities and industrial parks. Our wasteland is concrete and asphalt, a mix of rusted and new metal, wires, and lights. Twilight and headlights illuminate silhouettes of old bridges and empty factories.

This is far from barren. Instead of being the absence of civilization, it is a necessary byproduct and requirement. Landfills and logistics together, the two components meant to be invisible become the universal backdrop for everything. While New Jersey may offer the key example, this wasteland is everywhere with a few pockets of cities, housing developments, and wilderness. Now, how do we understand this bright wasteland?

Simply looking around at the rusted bridges and fourteen-wheelers is confirmation enough that the wasteland was produced and is constantly being made and remade. This process, even though it may at first feel as much, is not an entirely autonomous event, happening without our knowledge and activity; rather, it is through our everyday actions and the products of our activity that contribute to the wasteland. The corollary to this is that the wasteland is also a contributing factor to the production of ourselves. We make the wasteland and the wasteland makes us.

While in movies, the leather-laden and begoggled motorcyclists appear quite situated in their environment, how are we, coffee-stained and donning a singular air-pod in our Sedans situated in our wasteland? Mark Fisher's "capitalist realism," that it is easier to imagine the end of the world instead of any alternative, and Zizek's claim that we are all Fukuyamaists, that we all tacitly believe that we are at the end of history despite our conscious beliefs otherwise, both capture the real character of this wasteland: the fact that it can never be recognized as such. To do so is to finally address the concrete reality of the wasteland, of the ruins of what was before, and the possibility of what can come after.

This is precisely the radical freedom prompted by science fiction fantasies of "terraforming." Here, humans find an inhospitable planet and then seek to create a suitable ecosystem and habitat for human life. Is the proper post-apocalyptic response not one of terraforming, of accepting our wasteland as a wasteland and opening it up to our own will? The only issue with such fantasies is that they are always plagued by what the terraformers brought with them, such as their politics, petty disputes, and antiquated social systems. Is the problem then that, at least in these fantasies, the wasteland and its preceding apocalypse wasn't quite so catastrophic? To be more precise, it was not let go, what was not "laid to waste" that is the issue, not the inhospitable wasteland itself.

Yet, one has to be careful here. This point can easily be overemphasized into a glee of destruction (i.e., Benjamin's The Destructive Character, or Nietzsche's "putting one's shoulder to the plow). While there is some truth to this position, the path forward lies not only in the act of lying to waste, but, according to Marx, is "the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands." It is here precisely that the "laying to waste" is the antiquated apocalypse itself, the fact that the catastrophe was an element of yesterday despite its capacity to lay the grounds for tomorrow.

This point can best be made by Nicholas Hoult's Nux in Mad Max Fury Road (2015). In the film, Nux is a tumor-ridden and therefore doomed War Boy who comes to doubt his religious fealty to Immortal Joe and eventually sacrifices himself for the survival of a new society where water is freely given to all inhabitants of the Citadel. However, it is important to note that Nux, upon his sacrifice, screams his famous "witness me!" that all War Boys scream when death is imminent. Rather than having given up his faith and simply destroying the social structure his faith was integral to, Nux's sacrifice is his final proclamation of his faith and the preceding society, its own death blow to itself. In this view, the (de)constructive force behind the wastelands is society's own death blow to itself, one that should not be hindered, but aided for the freedom that follows from the ensuing terraforming and building of something new.

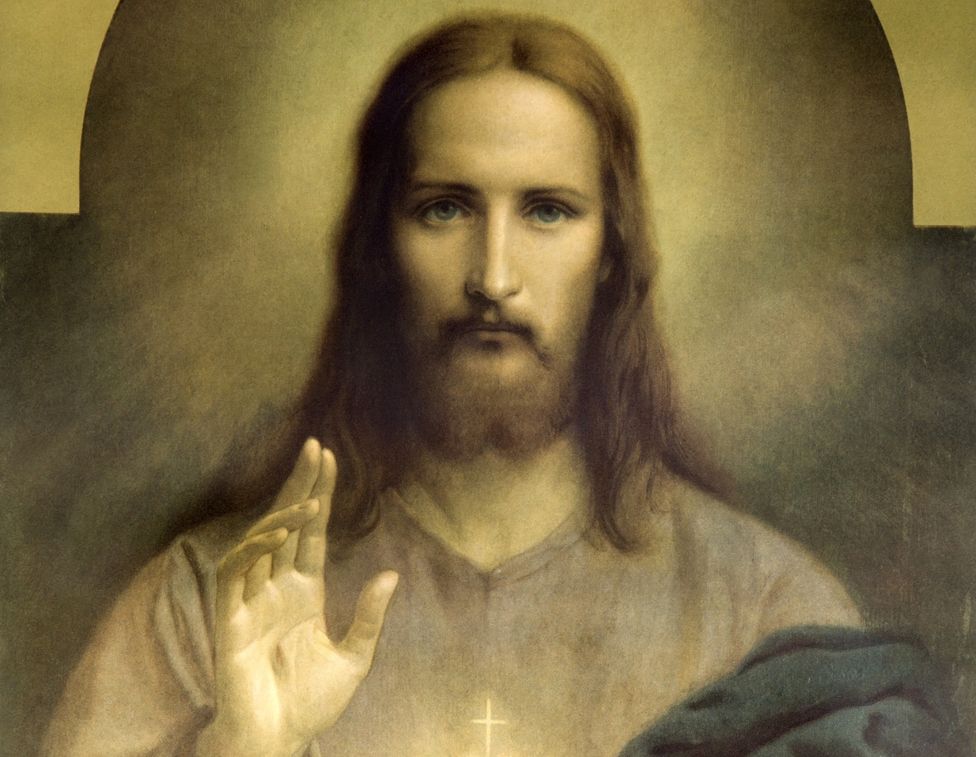

Love Island Teaches Us More About Jesus' Love than the Average Christian Sermon

by SoupWanderer /

2021-10-24

Love Island is a show that has captured my interest ever since the world started watching it during the COVID-19 pandemic. The premise is sickeningly schmaltzy. A dozen hot British (although the franchise has gone international) people do nothing but lounge around in pools wearing fast-fashion bikinis most likely assembled by women in the Global South while trying to find that one thing every person craves under alienated capitalist society: true love!

When one first starts watching the show, you feel really, really good about yourself. No matter how dense or helpless you may consider yourself to be, you can rest assured that your depth as a human being most likely surpasses the people on this show, who are quite frankly dumb as rocks. All the women describe their desired type as “tall, dark and handsome”, and yet pretty much the only men this show sends in look like this:

Don’t even get me started on the disparity in looks between the men and the women! But that’s for another time. Most people who watch Love Island consider their viewership sinful; the implication is that being invested in the everyday shenanigans of this vapid bunch is something we should all be ashamed of. Yet personally, I consider Love Island to be redeeming to humanity - the deeper you go, the more self reflection it invites. At the beginning, you feel incredibly smug about yourself - watching these people flit about and sometimes talk for minutes on end about nothing other than how attracted they are to each other, you have to wonder: “Am I… better? Than… everyone?” And you certainly can’t be blamed for feeling that way! One is probably watching this show with friends, reflecting on how their everyday conversations are much deeper and more introspective. But this horribly shallow process, the “getting-to-know-you” stage, invites this sort of reaction precisely because we are self-conscious about our own shallow conversations that are simply not on display for the world to see. Think of the way one comports themselves in a brand new environment, be it a workplace, a school club, or a new partner’s family. Can many of us really say that our ice-breaker conversations are much more deep and profound than those of the people on this show? And as the show progresses, we do actually become invested in the people on this show. This season I fell in love with the emotionally intelligent gems Teddy and Millie, and the boundlessly effusive Jake and Liberty. I was incredibly let down by the flawed and fierce Faye, who struggles with so much self-loathing that she has to be cruel to those around her. I was disgusted by the actions of men like Liam and Tyler, who seriously made me consider the case for a matriarchal society. And I was baffled by the duo of Toby the clueless himbo, and the shrewd marketing executive Chloe, who for some reason fell for him. And ultimately, I do believe that Love Island forces us to turn a mirror upon ourselves and realize that none of us is more deserving of divine salvation than another. Merely by the way that the show displays people at their best and their worst (and the worst can be truly despicable), we are forced to confront our own past sins and follies. Some of them are more egregious than others, but I hearken again to the lesson of the Good Samaritan; are we really better than these people on the side of the road? If we ourselves are single, can we really say we are incapable of recognizing the desire for love and the mistakes we make to end our own loneliness? And if we are in a relationship, can we look upon its course and remark that it has been seamless and without trial? And when we see devastating breakups and affairs, do they not remind us that love itself is about opening your heart up to the possibility of ruin? Half of Love Island is about watching people who are very bad at being in relationships trying to discover how to actually make a relationship work with the person that they love - only every messy step is cast into stark relief on national television.

And for all the mess and drama, some people really do end happily. Some of these couples end up married and now have children. I think that when they do work out, they really exemplify how love is a feeling that is universal to us all - even the most foolish, vapid, and doltish people can find a permanent life partner. The path to that union is almost never perfect, but somehow they have managed to arrive. When it comes to falling in love (and sometimes even staying in it), Love Island shows us that no one is really better than anyone else at it. We may think ourselves much more noble and grand than the people on the screen, but their subsequent bonds humble us deeply - whether by reminding us of our own shortcomings, by showing us legitimate love in the face of all doubt, or by showcasing the shocking heartbreak that no one is safe from if they choose to love. It reminds us that in many of life’s emotional pursuits, anyone can end up battered and bloody on the side of the road - which is precisely why we must embody the Good Samaritan and extend our hand.

A wave can crash on a rock with the latter remaining unbothered, but certainly an unprovoked fist would cause shock if not immediate anger. In any conflict, the physical and mechanical actions are not enough. One doesn’t simply punch back and remain in the same state of mind as before. No, there needs to be a rationale, a reason. “We are fighting for…” or “The other side is…” Either one has proven useful in the past. Combatants don’t merely scramble for the nearest weapon to defend themselves with, but they also grasp at ideas to justify their actions. At first glance, this may seem a cynical “oh, any lie will do,” and speak to a hasty conclusion that all rationales are only incidental. Yet, this would miss the more interesting conclusion that myth is not simply a “lie,” but rather an expression of something very real. The concept of the myth as outlined by Georges Sorel and elaborated by José Carlos Mariátegui speaks to the power of a narrative not as a lie, but as a specific expression real conflict. Paradoxically, it is the socialist “myth” that can provide the most clarity and cut through the obscuring fantasies that fill our contemporary white noise.

To work through this, why not start in the most obvious place: stories of war. In their recent album The Great War, Sabaton, a Swedish metal band, recounts some of the more famous moments within WWI. Halfway through this recounting, the track “Great War” follows a soldier as he meditates on his involvement in the war. The song has him ask “Where is this greatness I’ve been told? / This is the lies that we’ve been sold/ Is this a worthy sacrifice?” Later in the song and through battle, he reaffirms his role, “I do my duties, pay the price / I’ll do the worthy sacrifice / I know my deeds are not in vain.” Here, there are two competing accounts of WWI. On the one hand, there is a cynical recognition that he was sold lies, yet on the other, he affirms that he is making a worthy sacrifice and that his deeds are not in vain.

There are a few possible readings of this contradiction. The first is that he simply comes to his senses and recognizes the truth, disavowing his earlier, panicked questioning. Aside from not being interesting, this reading doesn’t fully capture the truth that was uttered in his cynicism. The second would have him cling to the narrative so that his actions are not in vain, that instead of first believing he is being lied to, he chooses to lie to himself out of necessity. While this certainly has some merit, it misses the most important part of the track: that it is narrative that is adding to the ever-continuing story of war. Here, the fact that Sabaton is retelling, rephrasing, and reframing stories of war speaks to Walter Benjamin’s famous thesis that “the only writer of history with the gift of setting alight the sparks of hope in the past, is the one who is convinced of this: that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious.” Sabaton, and not the fictional protagonist of the song, is the one trying to “save the dead” by retelling the story in this way. In this reading, the solution to the cynical questions of the protagonist is answered by those who look to redeem the past.

Now, while Sabaton is providing a narrative of WWI regarding the “dead,” what is to be made of this lyrical narrative when regarding more typical arguments of class war? It is no secret that the Bolshevik revolution was partially incited because of the disaster that was WWI, so would not the easy, socialist response merely be “war is a capitalist phenomenon built on illusion that obscures the concrete potential for peace and harmony, and therefore we should expose this lie?” What this impulse leads to is a knee-jerk reaction, essentially arguing “yes, the bourgeois warmongers deal in illusions while socialists deal in science.” Somewhat similar to the modern liberal’s almost religious “I believe in science,” this impulse misses the understanding that, as Mariátegui puts it, “without myth, the history of humanity has no sense of history” (384). The key here is that there is no fleeing from fantasy into reality, but instead seeing how fantasy itself structures our reality. Our sense of history, and therefore a sense of self, is structured by myth. This is the reality, one that is penetrated and shaped by myth, not purely obscured by it. In this light, it is not that the hyper-nationalist narratives of WWI were true (far from it), but they were expressions of a real kernel of truth, that, as Lenin highlighted, was a concrete component of the larger class war. The Bolsheviks’ struggle against war was then not some pacifist dream of harmony that would result in the protesting of returning soldiers; rather, it was the forceful insistence that all the sacrifice during WWI would not be in vain and that only through a socialist revolution would the dead be safe.

In this view, the re-telling of history with the aim to elevate, redeem, and save the dead through myth has a two-fold function:

1. It provides a powerful narrative for combat that can propel activity through great sacrifice.

2. It paradoxically is an expression of a real kernel, that reality and history include myth, and therefore sidesteps the greatest fantasy of obtaining “pure,” “scientific reality.”

Is this not exactly the function of the famous socialist red flag? The red symbolizes the blood of all the workers who built this world and gave their lives fighting for a society made by and controlled by workers. The red flag provides a powerful, real myth of redemption, that the blood of all past workers and revolutionaries will be redeemed in the revolution that is to come. As opposed to a mere vision of a utopian future, a myth incorporates a sense of history that necessitates a forceful and vigorous recognition of the past and present. Do not the historical instances of the Battle of Blair Mountain, the Ludlow Massacre, Wounded Knee, and countless others inspire a very real rage? This socialist myth is not some abstract ideal that reality is measured by, but a concrete expression of a past and reality that includes the actions, feelings, and aspirations of real people. To get to this concrete reality, there is no other way except through myth.

I'll come out honestly and say that I really don't think Tayari Jones's An American Marriage lives up to the hype. I have no clue why Oprah picked it for her book club, nor why it received such effusive praise from outlets such as The New York Times and The Atlantic. Don't get me wrong, it is incredibly well written. The author is skilled at writing and the prose is vivid and beautiful. But for approximately ⅔ of the book, we are merely flicking through a plot that is grounded in horrific and timely circumstances, but that has a strange emptiness of soul. It is like looking at one of Celestial's poupees, which are perfectly adorable and artistic, but something is ever so slightly off.

Deciding you don't like a book is always a tricky situation, especially when it is being widely praised as "Brilliant and heartbreaking..." (USA Today) and "Epic... Transcendent... Triumphant..." (Elle). It's not really heartbreaking as it is frustrating, and it's not really triumphant. Where are these book reviewers getting their adjectives from?

Part of what makes the book simultaneously easy to flick through and hard to read is that two of the three narrators are not really likable nor engaging characters. Nearly every time I read anything by Andre, whose defining characteristic is being "sweet" (which apparently stands in place of any serious personality), my eyes glazed over and I just flicked for plot. Celestial is more real but difficult to sympathize with. My biggest problem with Celestial is that she is selfish, but doesn't commit to what she's selfish about! Since her relationship with her husband Roy is the most closely explored, we best understand why she ultimately ends their relationship after he is wrongfully imprisoned for half a decade, because as she says, "A marriage is more than your heart, it's your life. And we are not sharing ours". That I resonate with, that made sense to me. But instead of proceeding with a divorce, Celestial continues her relationship with Andre while keeping Roy in limbo. That makes no sense, and it makes the "love triangle" in this book feel seriously contrived. Seriously, this relationship is not a love triangle - it's more like a love anglerfish, where the union of Celestial and Andre is solid and whole, like a female anglerfish, while Roy is basically the tiny male anglerfish, desperately trying to hang on while withering away.

What makes a book good or bad? Is it just because the characters are likable or unlikable? Because we don't like where the plot ends up? Of course not - enjoyment is subjective, but quality is objective. I'll give you one thing that I consider a pretty big knock against the potential of the book - Tayari Jones spent one whole year researching America's prison industrial system, and it barely makes it into the book. She even acknowledges it herself in the post-book essay. And in general, that's probably where the book fails the most. It has lofty aspirations to talk about the prison system, class inequality, intergenerational trauma, and love. But it fails at seriously examining any of those things, most disappointingly of all, love! Making your characters talk about love with embroidered sentences does not convince me that they love each other. Half of the time that I read about Roy and Celestial say that they loved each other, I felt that they were trying to convince themselves and me, which doesn't make for a very strong case. Celestial seems self-aware of this towards the end; Roy, not so much. For me, that's disappointing. They're both far more caught up in their own aspirations to live a bourgeois life, to buy nicer houses and scale up their doll store. And maybe that is the ultimate takeaway from this book, which is about many things but is ultimately supposed to be about love. Maybe the ultimate takeaway is that to chase being a part of the bourgeoisie under capitalism requires you to be atomistic, and requires you to forsake the idea of loving someone unless all circumstances conveniently line up. If you want to start your career as an artist who embroiders Swarovski crystals on dolls, can you really afford to wait for a husband who's in jail, no matter how wrongfully he was convicted? Doesn't it make sense that you have to erase his existence to preserve your reputation as an artist extraordinaire, not the perpetual wife of a prisoner?

The book isn't all bad - one of the things I cherish the most is reading about the true love between Roy's working-class parents, Big Roy and Olive. If you decide to read this book, I recommend you really appreciate the sections about them. They teach us that love is not about convenience - it's about rolling with the punches of someone else's decisions and choosing to live your life alongside them, loving them so deeply that when they pass, a piece of you goes into the earth with them. It is something precious, that no Swarovski crystal nor Mercedes Benz can ever replace.

Cracks and wires are strewn across the dry landscape. Only hidden insects and a constant hum of electricity assure listeners that the location wasn't entirely devoid of life. In fact, it is very much alive. Past fires and droughts clear the way for solar and server farms. Signals race up and down columns of a vast, almost living network architecture. They speed across fiber-optic cables, past fields of industrialized mono-culture, and are rendered on screens as digital billboards. CALL 1-800-JESUS dissipates into pixels of pornography and pet videos. Messages and media bloom atop trunks of alloyed antennae and copper roots. The worlds of Bratton's Stack and McCarthy's Blood Meridian are fused through an array of technical hyperlinks, mirroring the outskirts of Gibson's Sprawl.

Discussion whether this points to an alternate future or some sci-fi scene only obscures the uneasy familiarity of the view. This world has been built, transmitted and distributed by old users to new. The labor of erecting cell-towers, extracting energy, and laying miles of cable under-girds systems of gigabytes and gig work. As a writer of "content," the meaning matters far less than the message. This "content" is directed to an audience, not of people, but to machines, to the algorithmic highways that direct flows of attention. If there is fact in the form of fiction, then "sponsored content" advertises more than it intends.

The ads and messages of our augmented reality disclose a set of social relations not all too alien from their physical counterparts. The incalculable amounts of people and their labor that render these networks and "adSense" analytics profitable in the first place are assumed. They are now background processes, flesh-and-blood daemons that generate profit when executed. A logic of a system, taking shape and forming out of the infernal twin metabolisms of exploitation and extraction, is beginning to cohere. Yet this system isn't virtual. It is not in some Matrix-mainframe, only reachable by lone-wolfs in mirrorshades.

It is seen on the highways, in RF-coded supply chains, in underground lithium deposits, in the servers that store this very website. Most importantly, however, it is ultimately contained in the sheer capacity of the people that bring these materials to life. If something new is desired, it can only be realized through the very power and strength that brought about this landscape. Only when ransomware attacks begin to look like general strikes is this capacity ready to be leveraged.

Sheridan’s Those Who Wish Me Dead surprisingly offers an enjoyable and rather ominous portrait of our current predicament. Spoiler warning: the movie follows a young boy and his father who are on the run from two hitmen who were supposedly hired by those implicated in the father’s financial investigation. After the father falls victim to the hitmen, the young boy, Connor (Finn Little), teams up with Hannah (Angelina Jolie), a firefighter haunted by her past failures, to survive through the night.Though criticized as being a “90s style action film,” Those Who Wish Me Dead presents two contradictory viewings that both have a bearing on the “90s” style critique.

The first viewing, perhaps the more critical of the two, lies in how the film still has a naive hope that once the large conspiracy involving the wealthy and powerful comes to light, the problem will magically be solved. If this doesn’t scream 90’s-Clintonite-the-power-of-journalism, I don’t know what does. Either way, the film abruptly ends with Hannah and Connor affirming that they will make it through an uncertain future as a news van rolls up to heroically solve the political crisis and “keep the powerful accountable.” In this viewing, the film had the holy trinity of police, firefighters, and the press. Not only are cops and the forest service here to protect us from fires and bad guys, but the press will surely make those who had the father killed face the utmost scrutiny. I’m sure an avid Biden supporter will sleep easy tonight.

The second view involves the sense of uncertainty throughout the film. There is undoubtedly a sense of confusion surrounding the roles of the characters. The sheriff, (Jon Bernthal, whose image of the The Punisher still haunted his role), though at first playing a paternal and concerned role for Hannah winds up being rather inconsequential. This is especially the case when compared to his pregnant wife, Allison (Medina Senghore), who single-handedly defends herself from the hitmen, maims one of them, and ends up dispatching Aiden Gillen. Later, long after the radio confirms that the fire started by the hitmen is “0% contained,” firefighters are seen triumphantly parachuting out of an airplane over a desolate field of ash. One can’t help but feel that these too were somewhat inconsequential. Last but not least, the press van simply shows up and does nothing further than to, with a flourish of seriousness that only news commentators can employ, slam the doors of the van and rush off screen. I don’t even need to elaborate on the feats accomplished by these heroes.

In this view, the 90’s era component lies more in Fukuyama’s famous (albeit misunderstood) “the end of history” than in any well-worn cliches. The world inhabited in this second viewing is haunted by past fires and failings. The constant headlines of scandals and conspiracies are too common to mean anything – one only has to look at Epstein, Snowden, or the Panama Papers to understand that. The police, firefighters, and press are always-already too late. What does this mean? The crime already happened. The fire has swept through leaving only ash. The police can only meander through a crime scene and knowingly assess the severity (if they weren’t the ones that committed it in the first place). So what lies ahead? The film surprisingly offers a glimpse at a collective path forward with Hannah and Connor’s affirmation that they will make it through together. Though, perhaps more importantly is Allison’s survivalist capacity to defend herself, persist despite the world burning around her, and defiantly offer up the best one-liner of the movie, “this place hates you too.” Presented by her sheer capability is a path forward that leverages the rage of the burned, exploited, and largely abandoned hinterland. Perhaps the fact that I am writing this review from the deep woods of the Northern Midwest colors my view, but the film’s collective affirmation, survivalist defiance, and persistence all amid an inferno made for a compelling and overdue 90s flick.

That would be nice... Of course, I know my beliefs, as they are structured, researched, forged in the flames of imagined debates with inept foes. When I call myself a socialist, I thoroughly mean... This tree looks quite nice what kind of tree is it? Must be a birch. Hmmm, a beer sounds really good right about now...

Such are the cogent thoughts of an ideologue. Left on their own, thoughts tend to swirl, blend into one another, and trail off, never to be found again. Yet, in writing, such as this particular paragraph, a thought is made concrete, however partial. Through the reflection of writing, language can be wrestled with, fashioned to look one way or another. Moreover, this writing or language is not solely the intellectual property of each of us, all developing our own proprietary language ™ (at least not yet). It is external, made by others, developed over time, and objective, in the sense that they "exist" as an object in our mind.

I say all this nonsense to really remark on this weird world of blogging. This is not putting "pen to paper," but rather slamming away at a keyboard, writing in HTML because of the way I naively set up the SQL database behind this website. It could hardly be said that I am writing in "English." In fact, as others would remark, I am not. Either way, the consideration of "writing" now involves thinking through and coding just how exactly thoughts are to be presented, structured, datafied and stored. This even says nothing of how they are being algorithmically flung around, hyperlinked, and perhaps even turned into memes.

While this all sounds rather 2000s or earlier (admittedly, even the word "blog" sounds dated now), this conversation is far more relevant today. The behemoths of Facebook, Twitter, Google, and many others enter this very intimate flurry of thoughts. My previous stream of consciousness can now possibly be read as various potentials for tweets. Rather than fashioning some sense out of a chaotic flurry, this constant circulation of text becomes "content" to be commodified and endlessly passed around. Part of the "mission" of this site is to see a way out of this. This being said, I'm not too deluded into thinking that this "writing" will offer clarity in this goal. If anything, putting an abrupt end to this circulation will likely do more good than this. Despite these facts, this writing is not necessarily geared towards a target audience or is a strategic piece of "content" (I already do that as a copywriter); instead, this is an act of "writing" with the aim to eventually make sense.